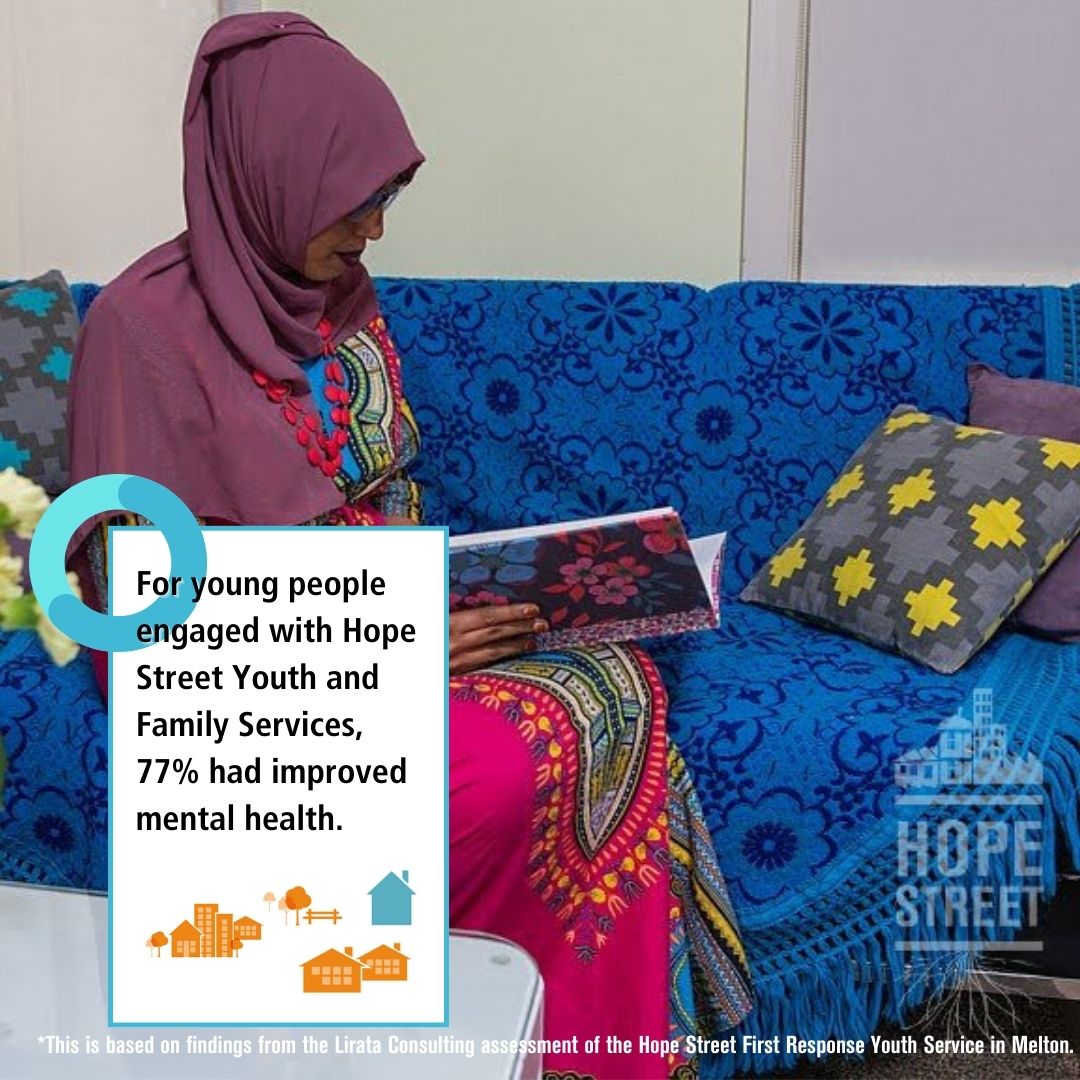

October 10th is both World Mental Health Day and World Homeless Day. At Hope Street, young people experiencing homelessness are supported through counselling and a safe place stay. It is well understood that individuals with mental health conditions are at heightened risk of homelessness and that, in turn, homelessness exacerbates the risk and severity of mental illness.

*Originally published in Volume 37- Issue 3, edition of Parity, Chapter 3.

Comprehending the missing pieces of the mental health system and youth homelessness services begins with early intervention psychological and mental health support with established community outreach services and local GPs. Fair and equitable access to mental health services is vital to ensure at risk vulnerable young people receive the services they need to function day to day. This starts with access to bulk-billing doctors. Unfortunately, many young people find such services out of reach due to cost and a lack of established connections to primary healthcare providers which makes it difficult for young people to keep track of their health conditions or to receive a mental health care plan for better targeted health care.

In Victoria, the Inquiry into Homelessness and Royal Commission into Mental Health, highlighted that primary health services, mental health plans and youth homelessness services are inherently linked to affordable medical treatment from bulk-billing GPs and a long-term plan to provide support to people that present to services, beyond just 10 sessions. The need for better healthcare for vulnerable young people to succeed with interdependent living is connected to robust housing solutions with wrap around support services.

It is well understood that individuals with mental health conditions are at heightened risk of homelessness, and in turn, homelessness exasperates the risk of and severity of mental illness. This is so evident that the CEO of Mental Health Australia Frank Quinlan stated, “poor housing and housing stress, together with other life stresses, reduce psychological wellbeing and exacerbate mental illness”. Yet, those who are recognised as being at such heightened risk, or presently experiencing such severity, find it the most difficult to access robust, best practice services primarily due to the unaffordability of health care and early intervention mental health support.

There are many conversations, reports and papers in the media, unions, social services sectors and individuals on the strain on health and support services for the working poor, people on social benefits and income poor people. From these reports and Hope Street experience with young people the norm seems to be extended wait times, sometimes more than 6 months, financial out of pocket cost to access general or specialist medical care. While there was an increase to the Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS) bulk billing incentive payments in November 2023 for concession card holders and children under 16, it remains difficult to see improvement in affordability for the young people and children who Hope Street provide essential support. With no demographic experiencing this harsh reality greater than those experiencing homelessness, the most severe being unaccompanied children and young people experiencing homelessness who lack the knowledge or finances to navigate the health care system.

On the 3rd of February 2021 the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System delivered its final report with recommendations grouped around four key features:

· 1. A responsive and integrated system with community at its heart.

· 2. A system attuned to promoting inclusion and addressing inequalities.

· 3. Re-established public confidence through prioritisation and collaboration.

· 4. Contemporary and adaptable services.

On the surface, there appears to be strong, proactive recognition and prioritisation of mental health in the community. Yet what Hope Street Youth and Family Services team members witness is the harsh reality that those in most in need of services face the greatest barriers in accessing services. Hope Street is not isolated in this experience, according to Orygen’s ‘Productivity Commission Draft Report into the Social and Economic Benefits of Mental Health, the provision of accessible mental health services for young people is outlined in their submission to the Productivity Commission. ‘Many young people do not seek help. Young people aged 15-24 with a mental health condition were almost twice as likely to not see a GP because of cost barriers compared with those without a mental health condition and two and a half times more likely to delay or not get prescribed medication due to cost compared with those without a mental health condition.’

As always, the answer sits with greater funding, advocacy, and prioritisation by all levels of government regardless of political party. As service providers inter-organisational collaboration and wrap around (multidisciplinary) support is essential to assist and resource young people and children to overcome their hardships and promote multidimensional self-actualisation. In practice, as a service model, Hope Street provides young people with residential support workers, case managers, youth reconciliation (counselling) practitioner and the Bolton Clarke Nurse, as well as link in support to other services such as a local GP. The challenge is that more funding is needed for mental health services to support young people with no wait times. This would mean bolstering the workforce responding to youth homelessness with a robust mental health practitioner workforce for early intervention. Arguably, there needs to be more funding for early-intervention mental health support specific to the established youth homelessness service providers, across Victoria and around Australia. A significant gap for young people experiencing acute mental health issues and presenting to psychiatric wards is a specialist who can liaise between homelessness service providers, social services and mental health practitioners. There is a lack of homelessness specific understanding for mental health practitioners, currently there is no designated role in psychiatric units dedicated to servicing the youth homelessness service sector .

According to Orygen’s Productivity Commissioner Draft Report into the Social and Economic Benefits of Mental Health: ‘Young people aged 15-24 with a mental health condition were almost twice as likely to not see a GP because of cost barriers compared with those without a mental health condition and two and a half times more likely to delay or not get prescribed medication due to cost compared with those without a mental health condition.’ (Orygen Institute, Health Economics and Cost).

To access primary youth mental health services, commonly a mental health treatment plan is the first hurdle to overcome. Having a young person willfully engage with a GP to ascertain the mental health treatment plan can encounter the barriers of their own historical marginalisation or trauma through self-recognition, then financial. If a bulk billing clinic is in an organisation’s local area it can make it more affordable for clients, if not, then State Government must do more to organise how accessible GP clinics are to different areas and provide incentives for affordable bulk-billing GP clinics to operate and provide primary care. “Early intervention for young people experiencing mental health issues and other health issues during or after homelessness is a means to prevent their healthcare from deteriorating further.”- Sue Scott, Operations Manager, Hope Street.

In Victoria, there is a need for healthcare reform that protects through legislation, the right to accessible medical care, including mental health services that is affordable and acts as a means of early intervention before a young person experiences an acute mental health issue due to a lack of affordable services. The protection of young people on low incomes to receive State funded mental healthcare would alleviate pressure on the already strained hospital system. Headspace confirms the link between homelessness and mental illness for young people: ‘Homelessness is a risk factor for mental and physical ill-health and mental illness is a risk factor for homelessness. 48-82% of homeless young people have a diagnosable mental illness (including mood, anxiety, substance use and post-traumatic stress disorders),’ the lack of adequate funding for specialist services that provide support to this vulnerable cohort is not acceptable and further marginalises young people and increases the risk of homelessness and acute mental health issues.

“Due to a lack of support and a lack of sustainable housing options for young people with complex mental health issues and / or emerging psychological issues, the risk of becoming homeless long term inevitably increases. This is a loss of opportunity and an immediate and short to long-term cost to community as vulnerable people continue to remain disconnected from society and their health and mental health further deteriorates.” Sue Scott, Operations Manager, Hope Street Youth and Family Services.

To link a young person to mental health support has its challenges, due to financial constraints and due to private providers being unable to accommodate at risk young people experiencing homelessness that are on low-income. The health care and mental health services infrastructure that accommodates young people experiencing or at risk of homelessness needs to be protected by legislation to ensure that as Victoria grows in population and urban spawl, services can match the community's demand.

At present, Hope Street has two successful models that have been tested, one for 10 years and one for over 30years, to provide support for young people with general and specialist health crises as well as dual diagnosis crises. The Homelessness Youth Dual Diagnosis Initiative (HYDDI), and the Youth Homelessness Community Nurse, referred to as the ‘Bolton Clarke Nurse,’ has demonstrated its enormous benefit to a young person’s health with flow on economic benefits to the wider community. Based on a youth crisis (refuge) service co-location model to respond immediately to young people’s needs when at crisis point and first entry to the youth homelessness sector these two specialist health programs are unique and highly successful. “To complement the youth homelessness services sector, these models can be scaled up across Victoria and around Australia with adequate funding. The ideal outcome would be to scale up these successful service models to enhance the current system, which has significant gaps due to lack of funding. This service model could be matched with opportunities for long-term social housing options including wrap-around support and would work directly with youth homelessness service providers and their in-house mental health teams, public healthcare providers such as GPs, hospitals and youth psychologists.” Sue Scott, Operations Manager, Hope Street Youth and Family Services. Currently, the need for the continued successful models to be funded and scaled up are the HYDDI model and the Bolton Clarke Homeless Persons Program Youth Nurse service is evident in the demand for youth homelessness services and the intersection between homelessness and health, including mental health.

It is fortunate that in Hope Street Youth & Family Services’ case they have a strong relationship with a local area clinic where they have willingly provided bulk billing exclusively to clients in the inner Northwestern metro area, however, this isn’t guaranteed for all services and is a testament to said clinics proactive community care. Following accessing the clinic and gaining a mental health treatment plan, the primary barriers are now presented. Wait times following referral, and support options. The mental health treatment plan, being part of the Better Access Initiative, entitles an individual up to 10 individual and 10 group sessions with a mental health professional in a calendar year, starting with 6 sessions then a review by the referring doctor to determine if the further sessions are required. These sessions are subsidised or free, however, if there are any mental health services in one’s area providing free support then commonly, they have the greatest wait times (with no prioritisation on vulnerability) and following sessions being subsidised there can still be an out-of-pocket cost anywhere between $70-150 per session. An unsurmountable expense when a young person’s weekly income is $256 per week and shelter and food are an essential priority.

Finally, if some of the most vulnerable individuals are unable to access responsive mental health support due to excessive wait periods (3-6+months) they can continually destabilise to the point of becoming acute (significant and distressing symptoms requiring immediate treatment), requiring the Youth Assessment & Treatment Team (YATT) or police connecting to the area mental health triage, potentially leading to compulsory assessment and treatment as per the Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022. At this point the cost to the wider community increases significantly, when it could have been prevented.

This overview serves the stark reality that many homeless young people encounter when navigating their mental health journey. That is, the difficulty to proactively engage with general and specialist health services, to the point where one destabilises and support is mandated for them, commonly reported as a de-humanising experience, regardless of legitimacy of care. The situation is also exacerbated by the housing crisis, severe poverty, cost of living crisis and social isolation.

During this current housing and mental health crisis, services on the ground must be a government priority. In the Northeast areas of Melbourne, Hope Street Youth and Family Services is fortunate to have a Youth Reconciliation Practitioner to provide free, accessible counselling to young people experiencing homelessness. The need to have responsive, robust mental health support where it can meet young people in safe and neutral locations only highlights the clear need for further expansion of this role to encompass a team of practitioners, rather than a handful of youth and family reconciliation practitioners funded through specialist homelessness dollars, scattered across various metropolitan regions. Commonly, Hope Street young people are deemed too complex when referred to ongoing, youth focused services (public or private) and it has resulted in area mental health triage direction to contain young people as long as possible, then escalate to police when they become acute. This is neither sustainable nor acceptable for a youth mental health ecosystem. Now, more than ever, there needs to be strong, clear leadership standing up for the most vulnerable members of society, signaling to young people they are valued citizens as part of this community and that they can provide value to the community. Developing the youth homelessness workforce requires career pathways for more psychologists and mental health practitioners that specialise in youth homelessness. In reflection of the Royal Commission, resources must support the growth of the mental health workforce to provide comprehensive services to the youth homelessness sector.

Solutions need to also include a greater expansion of youth services, significantly increasing capacity to provide youth focused support, specialist youth accommodation and housing options for young vulnerable Australians. This is paramount to lifting Australia towards its mantra of equity, opportunity, and a fair go. A lack of action on community, State and Federal levels to provide early intervention mental health in tandem with housing options, further marginalises an already vulnerable population in crisis and prevents them from achieving their full potential as valued citizens.